Fantasia Festival 2021 Film Review: The Night House

The Night House is a well-oiled scare machine powered by Rebecca Hall

The Night House flips the script on haunted abodes with chilling efficiency. Powered by a singular, wrenching performance from Rebecca Hall, director David Bruckner’s latest explores the spaces between terrifying, grief-fueled dreamscapes. Minor spoilers ahead…

The Night House, director David Bruckner’s latest nerve-jangling haunted house thriller, is a marvel of horror engineering. Taking the cheapest and most tired genre convention - the jump scare - and turning it into a powerful metaphor for the seizing unpredictability of grief, the film weaves a harrowing tale that marries potent terror with a powerful performance. Pitting a phenomenal Rebecca Hall against the dark spaces of empty architecture and an unseen tormentor, The Night House is this year’s answer to The Invisible Man.

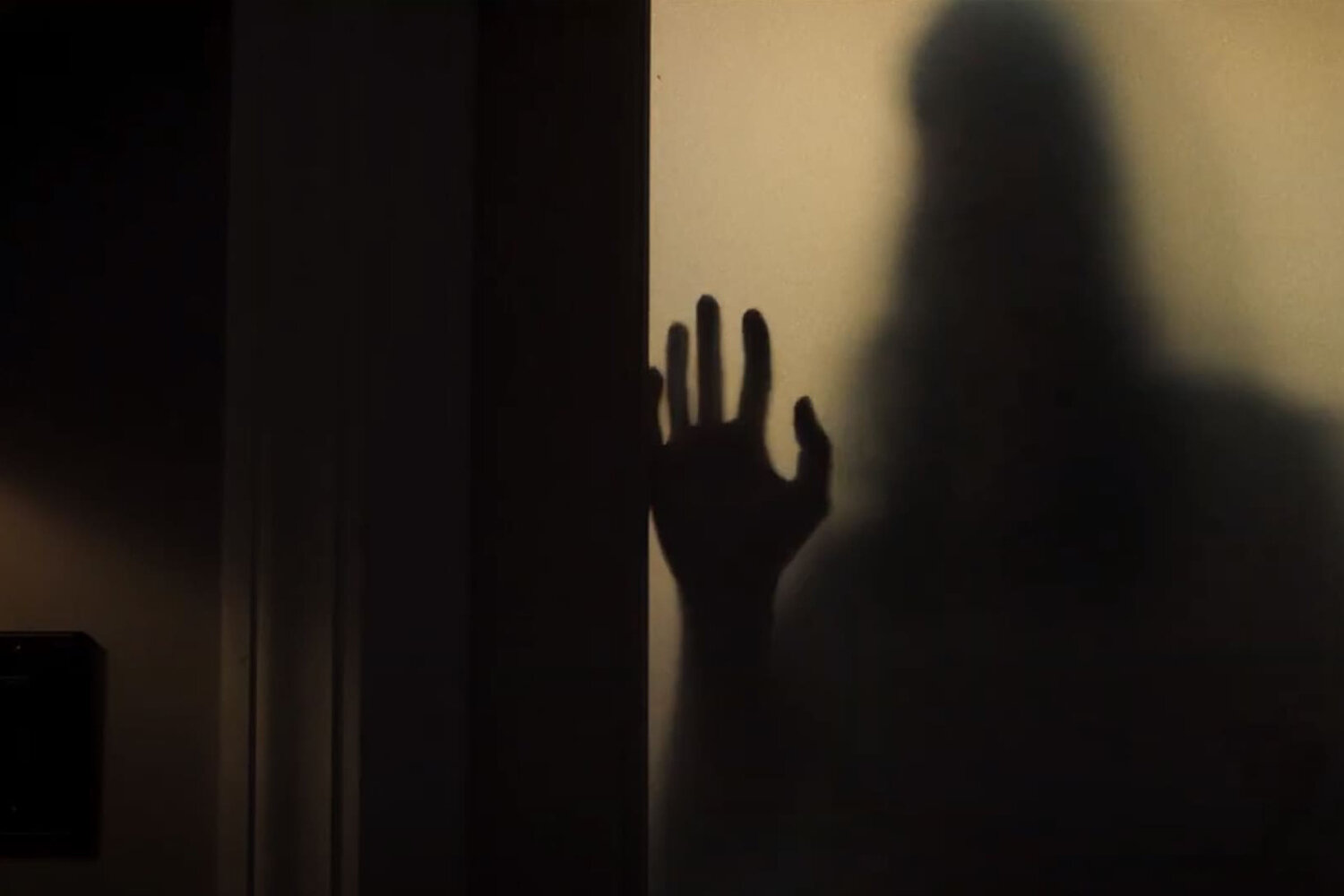

The Night House isn’t rewriting the horror playbook, but the way it melds its tropes with confident visual language and one of the best performances of the year is remarkable. The story is familiar: Beth (Rebecca Hall) is a recent widow whose husband Owen (Evan Jonigkeit) has inexplicably committed suicide. Beth, who always found Owen’s bright stability a counterweight to her own mercurial nature, is unmoored by the tragedy; she spends her days in the handsome lakeside home her husband built, trying to find the answers behind his violent death. It isn’t long before the space starts haunting her: the stereo turns on by itself to blare their wedding song, unexplained knocking and creaking reverberate through the wood floors, and bloody footprints appear and vanish from the dock. This unnerving phenomena also starts peeling away at Owen’s veneer, now laid bare after his passing. What’s up with his mysterious book of architectural sketches, laden with cryptic inscriptions? Do the compromising photos on his phone give way to even darker secrets? Is the horrifying apparition Beth sees (one of the film’s most clever uses of architecture and negative space) a visit from beyond the grave?

“Pitting a phenomenal Rebecca Hall against the dark spaces of empty architecture and an unseen tormentor, The Night House is this year’s answer to The Invisible Man”

Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski’s unsettling script throws a lot at you, but it’s Rebecca Hall’s singular, searing performance that anchors The Night House’s horrors. Hall, who is consistently the most interesting aspect of any project she undertakes, is in her element here, unraveling in a way not dissimilar from her roles in The Prestige or Christine. Locked in the throes of unshakable grief and bewildered by Owen’s sudden suicide, Hall’s Beth is a barely functioning person; her facade of pleasantries - even in the company of her best friend Claire (Sarah Goldberg) - barely contain the cauldron of torment within her. Vacillating between dangerous obsession and dry nonchalance (she mimes shooting herself in the head on more than a few occasions), Beth embodies a full spectrum of mourning. The Night House constructs a fascinating paradox: As moviegoers, we all want to see what terrors are teeming beneath the curtains, but at the same time, with Hall’s powerful turn as Beth, we - along with her friends and neighbors - beg to let sleeping dogs lie.

Like the most common pangs of all-encompassing grief, the terrors of The Night House emerge at night. On the surface, Bruckner runs the gauntlet of jump scares in the most conventional of ways: loud noises, cacophonous musical stings, elaborate fake-outs. But there’s a deftness to their construction that makes them feel earned; combined with Elisha Christian’s glacial cinematography, Bruckner allows the the camera to linger, breathe, and soak before scaring the pants off of you with a well-constructed scare. Or two. Or three. Or four. There are barrages of unrelenting jumps that will leave you breathless in the best way. The Night House also adeptly tinkers with the horrors of a shredded reality, disorienting with haunting liminal spaces that bridge the realms of wakefulness and ominous dreaming. What is real? What is a dream? It’s a question you’ll be asking yourself several times.

“…combined with Elisha Christian’s glacial cinematography, Bruckner allows the the camera to linger, breathe, and soak before scaring the pants off of you with a well-constructed scare.”

The Night House is impactful horror, but not everything about it works. Its wonky third act surprisingly - and unfortunately - veers a bit too far into the conventional, giving its narrative a concrete bogeyman it doesn’t particularly need. It also abandons numerous threads far more promising and interesting than the one explored in its rushed denouement: There’s a refreshing refusal to provide clear answers, opening up much of the film to interpretation, but there are also plenty of meaningful subplots just left dangling.

For all its trappings as a one-woman show, The Night House highlights the importance of human connection in the seas of grief and mourning. Instead of a mean-spirited ratcheting of a body count, the film finds salvation in having constants. The Night House - with crafted precision and Rebecca Hall’s arresting performance - conveys that houses aren’t the only things that can be haunted, but also delivers a reassuring message seldom seen in horror. Even with its bleak premise, spiraling protagonist, and heart-rending jump scares, it tells us: You don’t have to be alone.